Sometimes you only see how special something is when you look back at it later. Sometimes that something needs a hot second to properly settle into your subconscious. And that’s fine, I figure. I’d go so far as to say that, for me at least, be it because the job requires me to read rather a lot or not, it’s surprising to be struck by something straightaway. But even I didn’t need the benefit of retrospect to bring home how brilliant the Hugo Award-winning beginning of The Broken Earth was. I realised I was reading something remarkable—something “rich, relevant and resonant,” as I wrote in my review of The Fifth Season—before I’d seen the back of the first act, and when the full measure of the power of its perspectives was made plain, it became a comprehensive confirmation of N. K. Jemisin as one of our very finest fantasists.

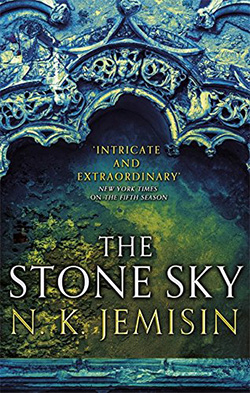

I stand by that, looking back—as I stand by my criticisms of its “surprisingly circumspect” successor. I said then that The Obelisk Gate sacrificed some The Fifth Season’s substance and sense of momentum to tell a slighter and slower story, and I’ll say that again today, never mind the passage of time or the news that it, too, just took home a Hugo. With The Stone Sky now behind me, however, and The Broken Sky closed, I do recognise that The Obelisk Gate played a pivotal role in the whole. It was the calm before the storm.

The Yumenes Rifting is the latest and the last of the apocalyptic events that have plagued the Stillness: a landscape ravaged by Seasons of madness, acid, fire and fungus, among others. People have passed away in their millions because of previous Seasons, but the Yumenes Rifting is different. If it continues, all life in the Stillness will be lost. Only a powerful orogene—someone with the ability to manipulate thermal and kinetic energy—could possibly stop it. Only someone like Essun, say.

But Essun, when last we left her, was at death’s door, having interfaced with “an arcane mechanism older than […] written history” named the obelisk gate in order to save the community of Castrima—albeit “at the cost of Castrima itself” and another, more personal price. When Essun awakens to find what’s left of her comm carrying her towards Yumenes and the rusting Rifting, she realises she’s slowly but surely turning to stone, like her late lover Alabaster before her. All she’s lost thus far is an arm, but every time she wields “enough of that strange silvery not-orogeny, which Alabaster called magic,” she’ll lose more, and come what may, it’s going to take a lot of that slippery stuff to save the day:

You’ve got a job to do, courtesy of Alabaster and the nebulous faction of stone eaters who’ve been quietly trying to end the ancient war between life and Father Earth. The job you have to do is the easier of the two, you think. Just catch the Moon. Seal the Yumenes Rifting. Reduce the current Season’s predicted impact from thousands or millions of years back down to something manageable—something the human race has a chance of surviving. End the Fifth Seasons for all time.

The job you want to do, though? Find Nassun, your daughter. Take her back from the man who murdered your son and dragged her halfway across the world in the middle of the apocalypse.

Little does Essun know that Nassun—like mother, like daughter—has taken matters into her own hands by calling upon the obelisks and stabbing her fundamentalist father with a shard of the sapphire. She didn’t want to do it, to be sure, but to survive, she had to. That just leaves her and Schaffa, the same so-called Guardian who was so cruel to Essun in her youth. Schaffa is trying to turn over a new leaf now, the better to make up for the many mistakes he’s made, and in Nassun, who has no one else, he sees redemption, yes, but more than that: he sees a chance to do something truly good for a girl who’s been broken by the same idiot bigotry he practiced in the past. To wit, he promises to protect her “till the world burns.”

As well it might if Nassun has her way, because she’s plum done. Done living in a world that treats people who are different like dirt; done living in a world that has taken away her mother and her baby brother and pushed her into patricide; done living in a world in which the only person who’s been there for her of late lives in perpetual pain; and done living in a world that punishes every living thing for no good reason that she sees.

But there is a reason the world—Evil Earth, as it’s known—is so hell-bent on hurting the few humans who have managed to survive the Seasons so far. These effects have a cause, of course, and it’s a cause rooted in the ancient history of the Stillness; a cause closely connected to the origins of orogeny. Several interludes set in Syl Anagist, the Stillness before it was stilled, introduce us to Houwha, a tuner created and controlled by a cadre of conductors. He and the others like him have been genetically engineered to bring a power source called the Plutonic Engine online. “This was what made them not the same kind of human as everyone else. Eventually: not as human as everyone else. Finally: not human at all.” And as above, so below.

Starting The Stone Sky, I made every effort to keep my expectations in check. I expected Jemisin to bring The Broken Earth’s core story to a close, but I wasn’t counting on the completeness of the closure this novel offers. I expected Nassun and Essun to cross paths at long last, but I couldn’t have imagined that their meeting would bring about “a battle for the fate of the world” that pairs the last parts of their catastrophic character arcs with some of the most incredible action seen in said series. It’s “such a terrible and magnificent thing to witness” that I sat stunned for some time after the fact, knowing full well what had happened but unable in the moment to comprehend just how—and how unexpectedly—it had.

I also expected the setting to be explored some more—and it is, physically, as Essun accompanies her adopted comm across the Merz Desert and into a false forest whilst Nassun and Schaffa pick their way through a breathtaking buried city towards Corepoint, where the crushing climax occurs—but I didn’t for a minute think that the author would devote such a substantial section of The Stone Sky to explaining how the Stillness itself came to be in delirious detail couched in characterful, if tragic context. Last but not least, learning anything at all about the beginnings of this trilogy’s terrific magic system caught me completely off-guard. That said, the answers aren’t unwelcome, and they go straight to the heart of the themes of the series.

As the conclusion to a trilogy that started strong and then stopped, The Stone Sky gave me everything that I wanted, and then it gave me more. It’s devastating. Poignant and personal and almost impossibly powerful. If my faith in N. K. Jemisin as one of our generation’s most able creators was in any way shaken by The Obelisk Gate—and I confess that it was, somewhat—then The Stone Sky has decimated those doubts. The Broken Earth is in totality one of the great trilogies of our time, and if all is well with the world, its thoroughly thrilling third volume should surely secure N. K. Jemisin a third Hugo Award.

The Stone Sky is available now from Orbit.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He lives with about a bazillion books, his better half and a certain sleekit wee beastie in the central belt of bonnie Scotland.

Pet (petty?) peeve about the use of the word “decimated.”

“The Stone Sky has decimated those doubts…” means it has reduced them by 10%. “Obliterated” would be a better choice.

I tried reading The Fifth Season after seeing online recommendations. There are some interesting concepts and characters in the book, but it was so slow-moving and disjointed that I barely finished it. A lot of time was spent in relationships and places that were unfulfilling and seemed to have little relevance to the overall story.

Reading that this second book in the series is a “slighter and slower story,” I don’t think I could stick it out to get to the conclusion of the story, despite the interesting aspects.

Ugh nemisin rocketed up to my favorite author as soon as I read the fifth season. I have this last installment waiting in my kindle and I’m freaking out! I don’t want it to end

Fantastic review, Niall!

Sad ending to a promising start.

Who’s who and in the last third, who gives?